Studying is straightforward.

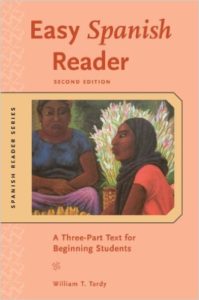

Welcome to another entry on how to study the Spanish language! We’ve just finished looking at the various methods we can employ in a study program spaced out over the course of a week. Click on this link to read the last entry (and the ones previous to that). In this chapter, we’re going to look at the issue of motivation to study Spanish.

It can be difficult to find motivation to study…

You may have been doing it a while and stalled. You may have never attempted. You might have even convinced yourself that it will never be an enjoyable prospect. But we need study to improve our Spanish! How do we get around this proverbial thorn?

The Basics of Approaching the Problem

Firstly, you have to come up with some semblance of a timetable or regimen and stick to it. You might have decided to allocate time to one-hour blocks, five times a week. You may have possibly made an agreement with yourself to study everyday for half an hour. It doesn’t really matter. What does matter though, is that you force yourself to sit down and actually do it.

Okay, so you just accept the road in front of you and sit down and do it, no questions asked? It seems like fair advice I suppose, but some people won’t find this enough to motivate them to study, and that’s also quite reasonable!

The Issue of Stress

Many people are hampered by stress. They stress about learning Spanish, and they find the idea of studying stressful, because they think studying itself is stressful. Notice how I said ‘think studying itself is stressful?’ That’s because studying is not really that stressful. People are more inclined to stress about stress, rather than the actual thing that they are stressing about. But once these people sit down and do said thing, they find that it’s actually no big deal. Here’s some food for thought:

“there is nothing to fear but fear itself” – Franklin D. Roosevelt at his inaugural speech.

“There is nothing to fear but fear itself”.

Is Spanish the real Enemy?

Some of you will be thinking ‘yeah right, easy for you to say. When I sit down to study, I don’t know where to start, and it’s frustrating because I can’t retain the information.’ It doesn’t have to be this way either. Instead of pummelling your mind with difficult-to-remember information, and making Spanish your enemy, bear in mind a few things:

Learning a language was difficult before you even decided to learn it. It has been, is, and always will be inherently challenging. So it’s best to forget that part, because it’s already a given reality that you can’t fight. You have chosen to take up learning a language, and it might be beneficial to instead see it as a hobby, and hobbies are supposed to be fun – they’re not tests. Which brings me to my next point.

We have to remember that the vast majority of us are not really being tested on any of this in a meaningful way (this might not be so applicable to university students and kids doing VCE or IB, but hey, the rest of the article has enough pointers to override this shortcoming!). Aside from the odd ‘test’ you might receive in your casual Spanish class, there are no real consequences for failing or not getting it right. There are, however, a million benefits for succeeding! Do I even need to list those? Therefore the only failure is not sitting down and having a go.

Are Long-term Goals really that useful?

While we’re on the topic of distancing ourselves for the idea that learning Spanish is somehow a test, this might be a good time to address the idea of goals. While it is good to have long-term goals, it could be advantageous to not see language acquisition entirely in this way. People spend years learning languages and they all end up at different places. There is no white line waiting for you at the end of your hard work many years from now. Bilingualism is not the Golden Fleece. It is a journey. Have your goals in the back of your mind, but don’t let them crush you before you get started, because there is so much fun to be had along the way…

Applying what we’ve learned…

So we know that Spanish is difficult, we have decided not to stress because it is all in our imagination, and we have resolved to not make the Spanish language our enemy. We’re also looking at Spanish as a hobby rather than an antagonist that wants to destroy us with its testing powers, or its suffocating goal-oriented centre. Furthermore, we’ve settled on having an honest go at the language, just for the hell of it! Now I hear you say “but it’s still going to be frustrating and hard, and I won’t be able to practically apply this information when I sit down to study.” Can’t you? I think you can.

We can bring together what we have discussed along with how we put pen to paper. Think of studying through the lens of a Taoist. The information on the paper, the grammar rule, and the audio exercise floating around somewhere in the ether are not going to kill you. Flow with the information that you read and write, and let it pass through you naturally, and in large volumes (i.e.: doing it everyday). Perhaps this is too abstract… Another way of looking at it is that you sometimes have to become mindless and carefree with your study, because remember, there is no stress, there is no enemy language, there is no test, requirement or need for learning this language, and there are no failures. Distance yourself from these ideas. Don’t think about all the negative and false implications about studying and learning. Instead, just do it. It’s actually simpler.

Bringing it all together practically…

Write out your verb tables a few times and just appreciate them for what they are. Forget everything else – just do them for the sake of doing them. If you get them wrong, forget it. Go and do something else Spanish-related and come back to them later. Remember…there is no stress. Listen to your audio exercises and enjoy the process of being involved with the learning process. If you don’t understand them, don’t worry. Go and do something else Spanish-related and come back to them in a couple of days. Think back…there is no enemy. Write out your compositions about your weekend activities because you like seeing new words, or making novel observations about the differences between English and Spanish. If you make a lot of mistakes or have to turn to the dictionary a million times, who cares? Remember…none of it matters. There is no exam, and there is no finish line – just you and a journey.

This doesn’t mean that you switch off when you study. The tasks you undertake will still be difficult at times, but as I have said, it is the idea of being difficult, or the idea of stress or failure which is more overpowering, but ultimately useless to the study process. Enjoy studying and absorb Spanish, its words, phrases and expressions and all the rest of it for what it is. Relish the volume, bathe in the hard work, and bask in the inevitable making of a million and one mistakes. None of it matters – it’s just you and a voyage through new ways of thinking and fresh insights…

Progress and Success will be yours

It is the process of switching off all the irrelevant ideas which ultimately leads to progress. Your involvement and engagement with the material, coupled with your relaxed attitude and a sense that this should be fun, with no consequences but positive ones, will result in success. Focusing on the journey will lead to the acquisition of new language skills over time. And here is the good part…

In becoming good at something, you will have developed a passion for it at the same time, because let’s face it – we tend to be passionate about the things we are good at.

Next week we will look at some of the day-to-day things you can do to incorporate Spanish into your life. Kind of like ‘studying without the work’!

¡Hasta la próxima!

Share this article!

ewed on their own. For anything to take effect, a catalyst needs to be added in the form of the ash from the quinoa tree, which goes by a number of names. This ash contains an enzyme which activates the narcotic. After chewing the leaves for a few minutes, the leafy, slimy mass is left between the gums and the cheek and…your mouth will go really numb, you may not want to eat for a while, and you may feel slightly more energetic. Just don’t kiss anyone whilst you’re doing this.

ewed on their own. For anything to take effect, a catalyst needs to be added in the form of the ash from the quinoa tree, which goes by a number of names. This ash contains an enzyme which activates the narcotic. After chewing the leaves for a few minutes, the leafy, slimy mass is left between the gums and the cheek and…your mouth will go really numb, you may not want to eat for a while, and you may feel slightly more energetic. Just don’t kiss anyone whilst you’re doing this. What’s unique about this tea is the customs and traditions built around it. Gourds come in all shapes, patterns, designs and sizes, and some of them are real works of art, as are the bombillas. Argentines and Uruguayans take a lot of pride in the daily ceremony of filling the gourd with the herb, steeping it in any number of idiosyncratic ways, before heading off to work, school or university, gourd and bombilla in hand, thermos in the other. Hordes of commuters can be seen in the morning on buses and on the metro, all sipping mate. Social events have a similar ritualistic atmosphere, where a single mate and bombilla are often passed around between friends.

What’s unique about this tea is the customs and traditions built around it. Gourds come in all shapes, patterns, designs and sizes, and some of them are real works of art, as are the bombillas. Argentines and Uruguayans take a lot of pride in the daily ceremony of filling the gourd with the herb, steeping it in any number of idiosyncratic ways, before heading off to work, school or university, gourd and bombilla in hand, thermos in the other. Hordes of commuters can be seen in the morning on buses and on the metro, all sipping mate. Social events have a similar ritualistic atmosphere, where a single mate and bombilla are often passed around between friends.